There was no vaccine for Sars or Mers. Will there be one for the new coronavirus?

- A month has passed since China locked down millions of people in Wuhan and other cities in Hubei at the heart of the epidemic

- In the first part of a series, the Post looks at how the race to find a vaccine may be different than for other coronaviruses

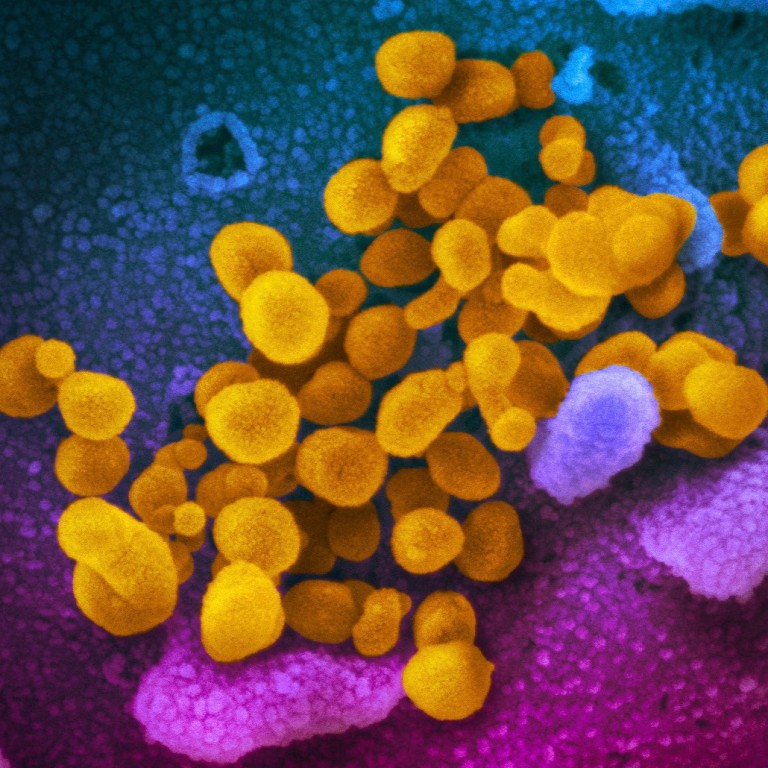

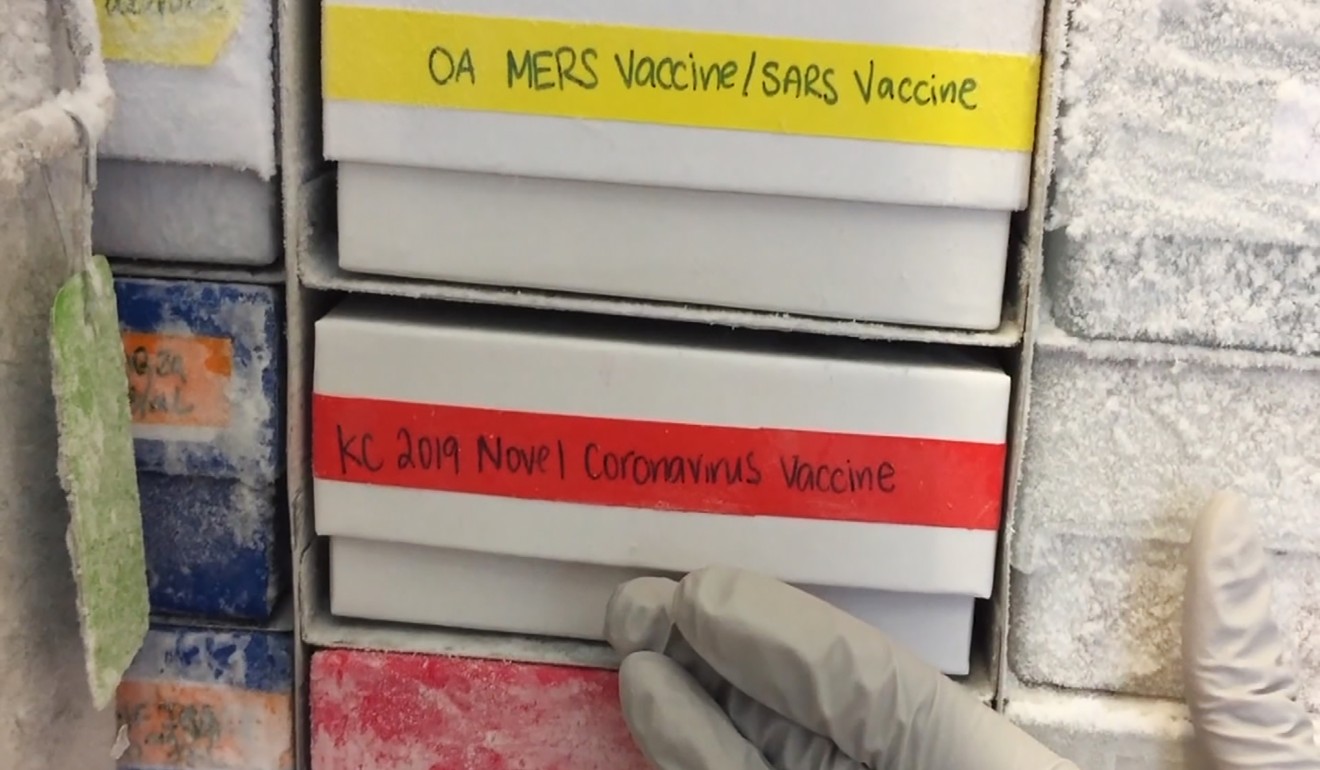

Seventeen years after the severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) outbreak and seven years since the first Middle East respiratory syndrome (Mers) case, there is still no coronavirus vaccine despite dozens of attempts to develop them.

As research institutes and companies around the world race to find potential vaccines for a new coronavirus strain that has infected nearly 80,000 people and claimed more than 2,000 lives, the question is, will this time be different?

Communicable disease outbreaks are handled by stopping transmission and with medicines and vaccines, but developing those vaccines takes time as they have to go through trials to ensure they are safe and effective.

They are also costly. According to Michael Osterholm, director of the Centre for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, it can cost as much as US$1 billion to develop, licence and manufacture a vaccine from scratch – including building a facility to produce it in.

For Sars in 2003, it took four months before the genome sequence of the coronavirus was available to develop antigens that could be used for animal and cell culture trials.

The first human trial of a possible Sars vaccine was conducted in Beijing in December 2004, but by that time the epidemic was over, and research into other diseases was given priority so it was shelved.

Coronavirus still stumps experts on when human carrier turns infectious

But the initial stage of the process has moved much faster for the new coronavirus than it did for Sars and Mers. Chinese researchers quickly isolated the strain and the genome sequence was released to the scientific community on January 10. That was well before the Chinese government announced the virus could be transmitted between humans, on January 21.

Funding also appears to be available, at least at this stage. With Beijing under huge pressure to control the epidemic that has stalled the economy for weeks, it has been willing to mobilise any resources it has for scientific research, and a special task force has been set up to coordinate efforts.

“Since the task force was set up, vaccine development has been a priority and we have pulled together all the best units in the country to work towards a breakthrough and to expedite the development of a vaccine,” Zhang Xinmin, director of the China National Centre for Biotechnology Development under the Ministry of Science and Technology, told the media on February 15.

Outside China, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) – a group backed by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Wellcome Trust and investments from various countries to speed up vaccine development – is funding institutes and companies including US firm Inovio Pharmaceuticals, a joint project by US firm Moderna and the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the University of Queensland.

CEPI wants to see if new platform technologies – which allow vaccines for different viruses to be developed in the same platform after some adjustments – can be applied to vaccine development for the new coronavirus, reducing the production time. The concept is similar to the one used in developing new seasonal influenza vaccines.

Animal trials begin

Less than two months after the new strain was identified on January 7, several institutes in China, the United States and Europe have already begun animal trials.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), five vaccine candidates have reached the preclinical stage, which involves cell culturing and animal trials to find out if they can induce immunity.

Moderna said it planned to start human trials in April, while a research team at Imperial College London indicated they hoped to begin human trials in summer.

China meanwhile announced on Friday that it aimed to conduct clinical tests on humans by mid- or late April. Xu Nanping, vice-minister of science and technology, said Chinese vaccine researchers had made progress at a similar pace to their international peers.

The speed is unprecedented – in the past, it would have taken a couple of years to get to the human trial stage. And previous attempts to find a coronavirus vaccine had only reached that stage, a meeting of the WHO in Geneva was told earlier this month.

Of the 33 vaccine candidates for Sars, only two reached clinical trials on humans, the rest stopped at the preclinical stage. For Mers, just three of the 48 vaccine candidates went to clinical trials on humans while the others only made it to the preclinical stage.

18 months away?

Speaking after the Geneva meeting last week, WHO director general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said a vaccine could be available in 18 months.

Tarik Jasarevic, a spokesman for the WHO, said: “It usually takes several years to develop a vaccine. We were able to shorten that in the development of the vaccine for Ebola by harnessing global efforts. We are already working to do the same for Covid-19.”

He said the WHO was expecting clinical trials on humans to start in three to four months.

Woman becomes first Singaporean to be diagnosed with both dengue and coronavirus

But some scientists said that timeline could be too ambitious as it was a complicated process to prove the safety and efficacy of a vaccine.

“Making a vaccine isn’t a simple process – first there needs to be a ‘candidate’ vaccine, with an appropriate manufacturing quality. This is then tested in animals to see if it seems to work,” said Allen Cheng, professor of infectious diseases epidemiology at Monash University in Australia.

“Then there need to be tests in humans to see that it elicits an immune system response, and to define the dose, then it needs to be tested in proper trials to see if it actually protects against infection and doesn’t cause side effects,” he said.

“Then it needs to be approved by regulators, and manufactured at scale, purchased by governments and deployed. This would usually take 10 years at a minimum. Even if everything goes perfectly … I would expect this would at least take a few years.”

The first Ebola vaccine was approved in December, five years after research first started, as the development process was delayed due to reported side effects in human trials. The WHO fast-tracked the approval process in the later stage.

Other experts who were more optimistic about the timeline said even in the best scenario, it would be impossible for the vaccine to be ready to deal with the current epidemic.

“I would expect to see a vaccine being commercially available in no sooner than a year if everything progresses without setback,” said Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Centre for Health Security.

“Though vaccine development is accelerating at a rapid pace, we cannot expect to have vaccine in sufficient quantities to be able to impact this initial stage of the outbreak.”

Peter Smith, a professor of tropical epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who sits in a specialist panel advising the WHO, said the later stages of human trials would not be possible this year.

“I would expect human studies on some candidates to start in the coming months, but the later stage studies which are required to test the safety and efficacy of a vaccine before licensure or widespread use seem unlikely to be completed this year,” he said.

Is it worth it?

Given that Sars disappeared after 2003, some have questioned whether it is worthwhile to pour money into vaccine development for another coronavirus. According to scientists, that depends on whether it comes back.

“If the epidemic is only for this year, then the answer is no. But if Covid-19 recurs, then the answer is yes,” said Stanley Plotkin, who had a key role in developing the rubella vaccine in the 1960s and is now a consultant for vaccine companies, as well as on the specialist panel advising the WHO.

Smith said if there was no recurrence next year it would be difficult to obtain data to test the efficacy of vaccine candidates in human trials.

“If conventional control procedures stop transmission of the new virus in the next few months then it may be that vaccine studies to establish efficacy in human populations will not be possible [until there is another outbreak],” he said.

“However, given the number of people already infected and the spread of the current outbreak, it seems to me unlikely that it will be brought to a rapid end, particularly if it spreads to countries with less well developed public health systems.”

Other experts agreed.

Adalja said: “The novel virus is spreading efficiently in communities – something Sars could never do. This will not disappear and there will be a continued push for a vaccine for some time.”

Chinese state media ‘humiliating’ nurses in virus propaganda campaign

Florian Krammer, a professor of microbiology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, who specialises in virology and vaccine development, said the coronavirus would probably last for several winters.

“Everybody is hoping that this can still be controlled, but the realistic chance that it can be controlled is low. So then what is going to happen is that this is going to spread worldwide, ” he said.

“If it does you might have an initial pandemic wave, but not everybody is getting infected and nobody has immunity, so it might be that this virus stays in the community and comes back in the northern hemisphere for the next few winters.”

Osterholm said the virus was transmitting like influenza, and it was increasingly obvious that containing its spread was impossible.

“The situation in China supports that this is more like influenza. No one has even proposed to stop seasonal influenza by doing the kind of interventions that have been done with this – social distancing, border closing, airport screening – and I think we’ve already seen initial containment hasn’t worked,” he said.

“This one may sustain itself in a very different way with a dynamic potential to be quickly transmitted. So it can’t be compared to Sars and Mers with that regard.”

But even if trials prove a candidate is safe and effective, having a vaccine ready to be used for a large population poses another challenge.

“Producing enough to vaccinate several hundreds of thousands of people may be much less challenging than producing sufficient quantities to vaccinate very large populations, using multiple batches of vaccine and requiring consistency testing between different vaccine batches,” Smith said.

Osterholm said: “Manufacturing these vaccines is not cheap and you have to have an approved facility, which is a very tough job to accomplish – you are talking well over US$500-700 million just for a building, and if you don’t have excess capacity that you can use now, it will take four to five years to build these facilities.”

Political incentive

Drew Thompson, visiting senior research fellow at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore and a former US defence department official responsible for managing relations with China, Taiwan and Mongolia, said there was strong political incentive for Beijing to carry through its vaccine development.

“If you think about the way the Communist Party thinks about legitimacy, successfully developing a vaccine independently would be a huge boost for China’s prestige, which matters to them a great deal. I can definitely see that being a top priority.”

Safety should also be a concern because vaccines are supposed to be given to a large number of healthy people.

“Vaccines are given to healthy individuals while small molecules [medicines] are given to someone who is already sick, so the risk calculus is different,” Adalja said.

Cheng noted that vaccination had a long-term impact on the human body.

“Vaccines work by ‘training’ the immune system with a part of, or weakened form of, the virus. In general the vaccine itself doesn’t persist in the body, but the immune cells do and provide protection against later infection,” Cheng said.

Chinese officials said they were trying to balance safety with the urgency of the situation.

“We have high quality R&D teams and we have vaccine manufacturers,” said Zhang, from the biotechnology development centre.

“But we must be aware that vaccines are a special product given to healthy people and safety must come first … Vaccine development must follow scientific procedures and strict management and we have to give scientific researchers time to come up with a safe and effective vaccine.”

Yan Jinghua, a vaccine expert with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, agreed.

“There is no approved vaccine for this coronavirus anywhere in the world yet, and that means there is a lack of experience and there is no risk assessment for the vaccine yet,” said Yan, speaking at the same press briefing as Zhang.

“It is a challenge for vaccine researchers. We have to have sufficient proof of the risks and benefits … safety is the number one concern – we want to have a licensed vaccine as soon as possible … but we have to make sure it is safe.”

The second part in the series looks at life under lockdown in Wuhan over the past month.

Purchase the China AI Report 2020 brought to you by SCMP Research and enjoy a 20% discount (original price US$400). This 60-page all new intelligence report gives you first-hand insights and analysis into the latest industry developments and intelligence about China AI. Get exclusive access to our webinars for continuous learning, and interact with China AI executives in live Q&A. Offer valid until 31 March 2020.